Human Elements in AI’s Binary World

Published:

As an international student stuck inside a dormitory from a foreign university during summer, I came to find vacations tedious. During the semester, when I don’t have my family around me, I still have my friends and people to interact with. During the break however, my human interaction is minimal, which is simultaneously peaceful but mundane. Because I’ve also had ample amount of free time lately, I happen to deliberate over that “human touch”, albeit regarding AI.

Recently, there’s been much endeavor towards humanizing AI in terms of aligning AI with human values and, more relevantly, making it sound or behave more like humans. But,is it worth sacrificing human touch for the efficiency gains brought by AI? Will AI ever replicate the emotional and cognitive aspects of human empathy? Do we even truly desire human touch in AI? These are some of the questions I’ll try to discuss. Despite my use of the word “AI”, I will emphasize mostly on conversational generative AI because AI’s inherent characteristics cannot be clearly assessed from non-generative tasks such as speech recognition, machine translation, and classification tasks, which have objective ground-truths.

How AI can Lack Human Touch

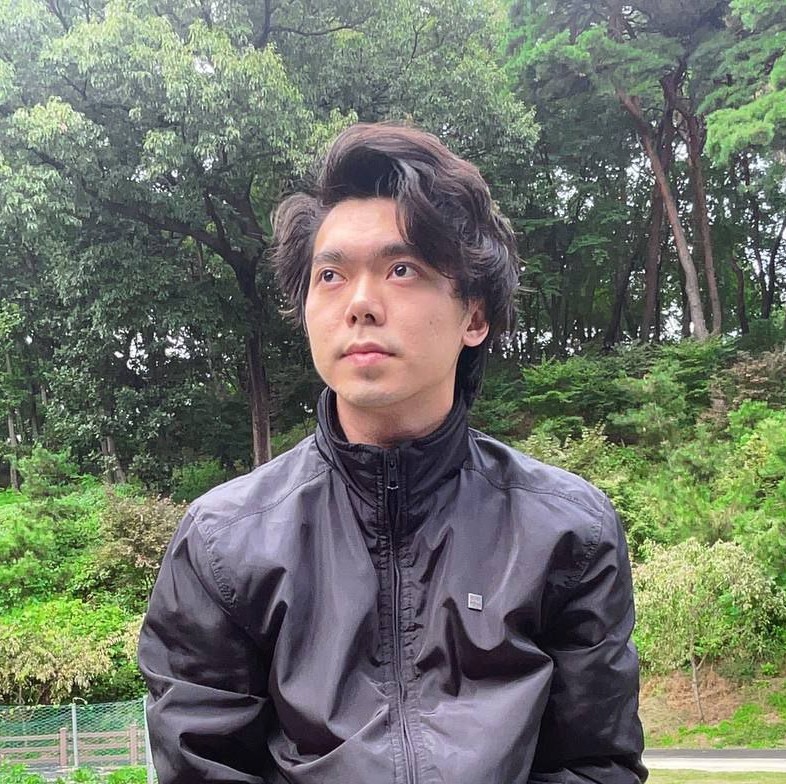

Now with the increasing odds that you interact with non-human subjects whenever you communicate with a system for some service, you may recognize that something in the interaction has been different. You can no longer ask for a discount or a size-up like you can do with a street food seller. There is no longer that awkwardness with the salesperson because AI is handling your transaction perfectly. You share your difficulties, but the listener AI is so logical that it comforts you with some empathetic sounding words and proceeds with suggesting what to do as if using a template. For example, the generated output from ChatGPT in Figure 1 is indeed a constructive response and does sound empathetic. But you don’t always seek logical suggestions when you get something off your chest, do you?

Fig 1. A response of default ChatGPT (GPT4-o) to a devastating news of the user

Fig 1. A response of default ChatGPT (GPT4-o) to a devastating news of the user

I feel that by unburdening ourselves, we want our problems or stories to be actually heard and expect the listeners to empathize with us. Humans are meant to be acknowledged and validated by others. Seeking external validation is an innate human tendency although it’s often portrayed as being overly dependent on others. However, conversational AI are trained, in general, with the objective to maximize its helpfulness (a bit simplification, see note [A]), which makes its responses centered around helpful suggestions although the prompt doesn’t explicitly ask for them. In other words, generic conversational chat-bots are designed to be practically helpful instead of acting as an emotionally supportive therapist. Therefore, understandably, chat-bots used for services like sales can lack human touch, which we don’t need but we are pleased when we experience it.

Here, we should consider whether it’s worth sacrificing the human touch for the efficiency gains (i.e. relying more on automated systems rather than humans). Regarding this trade-off, favoring efficiency in the domain where the human touch is not necessarily required can even yield a net positive outcome. Our main goal when inquiring about a product or asking for an explanation about a lecture is to acquire information or understand a concept respectively. Since we generally do not expect or need any empathetic responses in such cases, disregarding the use of efficient AI chat-bots solely for the lack of human touch is unreasonable. However, applying unempathetic AI in domains where empathy is required is not only counter-productive but also can be unethical.

Empathetic AI and Ethics

One good example of such a domain is health care, which will be examined in depth as a representative of “human-touch-required” domains. For now, let’s assume that AI chat-bots intended for health care are not empathetic enough, and the discussion of why it can be the case will be presented in the next section, where the possibility of empathetic AI is explored. Among the numerous types of human touch, empathy is arguably what matters most in health care. Empirical studies suggest that patients disclose their histories selectively to doctors according to how empathetic they perceive their physician to be [1]. In other words, they consciously or subconsciously tend not to reveal exact information until they sense that their physician is resonating with their story of pain or disease. Additionally, effective medical care depends on patients adhering to treatment. Indeed, poor results in medicine is mainly attributable to not following medical recommendations including prescriptions. The biggest predictor of adherence to treatment is trust in the physician, and trust turns out to relate with the patient’s perception that the physician is genuinely worried when they talk about something worrisome [2]. Therefore, if AI chat-bots become solely responsible for nursing patients and are not empathetic enough, the result can be unsatisfactory.

On the other hand, there has already been some evidence that robotic pets can keep elders with mild-to-moderate dementia company, decrease loneliness and improve well-being [3]. Hence, even if genuine empathy cannot be manifested by AI, one can still defend an empathetic AI program by the fact that even coming close to real empathy is good enough to produce the intended outcome in some cases like elderly care. However, it would raise ethical conflict to use seemingly empathetic AI for people who may believe that it is real and thus experience clinical benefits. Regarding the trade-off between beneficence and respect for patients, one author of In Principle Obstacles for Empathic AI [4] argued “When such beneficial results are based on deception, the violation of respect for persons is serious enough to shift to alternative means of decreasing loneliness such as supervised visits with real pets, or using AI to help people connect with real others.”

Will AI ever be Empathetic?

To analyze whether human touch can be integrated into AI, it’s important to think about what empathy actually is. Various definitions of empathy in the literature emphasize two key components: emotional empathy and cognitive empathy.

Emotional empathy is experiencing emotions by yourself resulting in empathetic concern for others. For example, when your friend opens up their dismay about exam results, you have developed emotional empathy if you also feel upset and, therefore, have concern for them.

Cognitive empathy allows us to detect or identify the emotional mental states of others based on features of their expressions. For instance, when you understand that your friend is truly dismayed due to their verbal or physical expression, it can be said that you are cognitively empathetic.

Psychopathic patients can still be cognitively empathetic while completely lacking the remorse associated with emotional empathy. Likewise, AI nowadays are pretty competent at sentiment analysis and can exhibit cognitive empathy since they can accurately predict the emotions of the speaker or the writer given a speech or a text. However, whether AI will ever have emotional empathy might be related to whether AI will ever be conscious. In fact, there’s so many aspects to discuss consciousness in AI that it deserves its own analysis. Until we have answers for at least the “pretty hard” problem in Figure 2, which is taken from the book, Life 3.0 Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, it’d be virtually impossible to know when or whether AI can be truly empathetic.

Fig 2. Classification of consciousness problems in Life 3.0 Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Max Tegmark

Fig 2. Classification of consciousness problems in Life 3.0 Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Max Tegmark

Response or Identity behind the Response

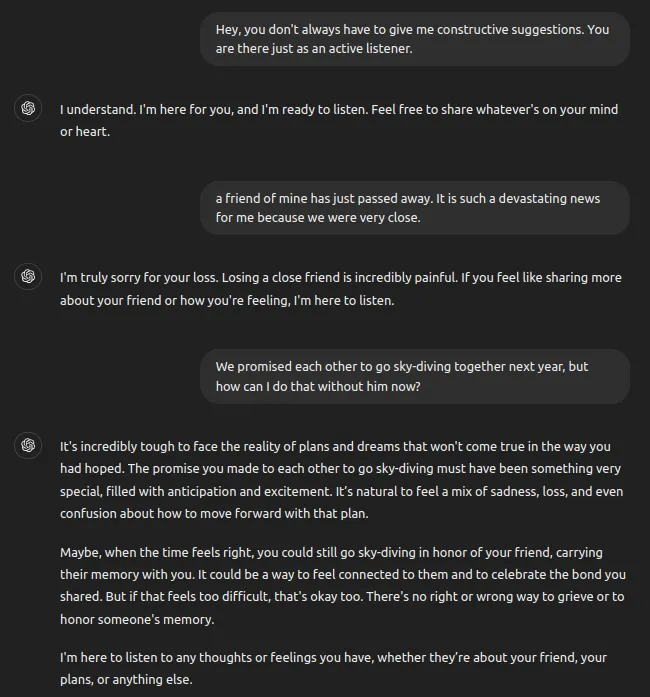

It can be a good idea to take a step back and ask “Is human touch in AI even what we actually desire?” Looking back to the ChatGPT’s response in Figure 1, you may argue it’s unfair to expect human touch in generic AI that’s supposed to be helpful. Valid point! We can actually ask AI to behave like a therapist or a better listener as in Figure 3 if a particular way of answering doesn’t resonate with you.

Fig 3. Responses of prompt-engineered ChatGPT (GPT4-o) to a devastating news of the user

Fig 3. Responses of prompt-engineered ChatGPT (GPT4-o) to a devastating news of the user

Surely, the response is much more comforting and validating, but would you feel any better if you were in this situation? I will leave the answer to you as we may have different answers. If you don’t feel any better like me, why is that? Is it because you know the subject responding back to you is non-conscious AI such that no matter how the response sounds empathetic, it feels hollow? On the other hand, getting a response even as short as “I know, right?” or “I understand you.” from the person you care can alleviate your pain much better. Then, it’s apparent that it is the identity behind the response that actually makes the difference, not the response itself. This is why it is still humans that we reach out to when we want to unburden our feelings while it is AI that we reach out to when we seek only for logical suggestions. However, whether it would still hold true in the realistic future teeming with AI of multimodality is more interesting.

We can see a glimpse of multimodal AI chat-bots becoming alternatives of human interactions coming if we look, for example, at AI romance apps like Loverse, a Japanese app allowing users to chat with AI avatars having an appearance and a personality. The creator of the app said, “The goal is to create opportunities for people to find true love when you can’t find it in the real world. But if you can fall in love with someone real, that’s much better.” [6] The main caveat in this belief though is the possibility of being stuck at a “local optimum”. Having a digital partner to chat with while waiting for a bus, for example, can be indeed fun (local optimum), but you can become so comfortable talking to AI that you find it too effort-consuming to interact with an actual person, which deters you from potentially having a profound and genuine pleasure (global optimum). In this case, AI chat-bots are analogous to social media and addictive games in that you use them to mediate your boredom but counter-intuitively hinder you from eliminating the root cause of your sluggishness. However, sometimes, you might want to choose to be content with sub-optimal solutions simply when searching for the global optimum is too expensive (computationally and/or time-wise) if you’re familiar with mathematical optimization. In such cases, AI chat-bots might be able to at least remedy your problem, but not eradicate it.

Machines Learning to Sacrifice

Another remarkable human element worth discussing is altruism, which is manifested in not only humans but also animals in general. For example, some ant species have workers that will sacrifice themselves to protect the colony from predators or invaders. By helping to raise their sisters and brothers (the queen ant being the common mother), worker ants indirectly pass on their genes, maximizing the colony’s overall genetic fitness. Can an AI agent exhibit such form of altruism? Here, this altruism is goal-oriented where the goal is to is to maximize the passing on of genes to future generations even though individual ants are not making conscious, rational decisions about these goals, but rather driven by innate genetics shaped by evolution to benefit the colony. In fact, the conditions under which such altruistic behavior will evolve can be formalized by Hamilton’s Rule.

r.B > C where r = genetic relatedness, B = benefit to the recipient, C = cost to the altruist

In principle, any phenomenon that can be formulated as an equation can be simulated given sufficient time and computational resource. Now that the variables, r, B, and C are declared, if only we can specify how to calculate values for them, an AI agent can develop this type of altruism.

However, the behaviors of some animals, most noticeably humans, are different, aren’t they? Despite not being related genetically, they sacrifice themselves for someone, expecting nothing in return except the benefit of the beneficiary. Some might argue that r should be broadly considered also as “closeness” to explain the propensity of sacrificing oneself for also those they are closed with such as friends or loved ones. Then, how will you explain with cases where one sacrifices their life to save a total stranger (fire-fighters for example)? In fact, single behaviors we choose are not the product of evolution, but what we’ve evolved is brains, which have certain inclination like being empathetic.

The questions do not lie not only in whether AI agents can ever be genuinely altruistic but also again in if we would even want AI agents to be altruistic. Most incarnation of altruism comes in the form of compromising your progress towards your goal. Some wonderful people make illogical sacrifices for others despite having their own “objective function” in life (eg. to achieve career success). If we can forever use AI as a tool (i.e. there won’t be conscious AI), it sounds counter-productive to allow them to compromise their objective since they are meant to serve a specific purpose. For instance, a self-driving car that regularly decelerates to let other cars overtake in traffic or a shopping AI agent that donates purchased items to the need on the way back home isn’t desirable, is it? For usefulness, we might prefer AI to be objective and task-focused rather than altruistic, and arguably a more important pursuit is to align AI with humans’ goals while instilling robust ethical frameworks in them.

Closing Thoughts

Realistically, it’s worthwhile to discuss how humans and AI can coexist for an indefinite future, especially considering AI’s inability to truly empathize. The general blueprint of such coexistence is wonderfully described in this Ted-Talk by Kai-Fu Lee [5]. In fact, advancing AI for the overall betterment of humanity is a fascinating quest in a way that it is intertwined with possibly every branch of science and even philosophy, as it touches on very fundamental questions of life such as what it means by consciousness and why human touch is so special. We may not have exact answers or reasons for those yet, but we all can feel that human touch is special whether it is physical or metaphorical. The future may not lie in perfectly replicating human touch in AI, but rather in developing a symbiotic relationship where AI enhances our productivity and capabilities while we maintain our unique capacity for emotional resonance and selfless act.

Thanks to friends of mine for reading the draft.

Notes

[A] Generally, instruct models like ChatGPT are fine-tuned to strike the balance among several traits, which can be 3H (Helpfulness, Harmlessness, and Honesty), instead of simply maximizing its helpfulness. However, depending on the trait we desired, we might prioritize helpfulness over harmlessness since these two traits are often mutually exclusive in some cases (eg. prompting for advice for illegal actions)

References

- [1] Eide et al. (2004) Listening for feelings: identifying and coding empathic and potential empathic opportunities in medical dialogues. Patient Educ Couns 54(3):291–297; Finset and Ørnes (2017) Empathy in the clinician-patient relationship: the role of reciprocal adjustments and processes of synchrony. J Patient Exp 4(2):64–68

- [2] Roter et al. (1997) Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med Care 36(8):1138–1161; Kim et al. (2004) The efects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof 27(3):237–251; Halpern, “Empathy and Patient–Physician Conficts, op.cit.

- [3] Portacolone et al. (2020). Ethical issues raised by the introduction of artifcial companions to older adults with cognitive impairment: a call for interdisciplinary collaborations. J Alzheimer’s Dis76:445–455

- [4] In principle obstacles for empathic AI: why we can’t replace human empathy in healthcare, SpringerLink, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00146-021-01230-z

- [5] How AI can save our humanity, Kai-Fu Lee, https://youtu.be/ajGgd9Ld-Wc?si=Zjg7OfQTrKmJG628

- [6] Independent (2024), Japanese AI dating app that boasts over 5,000 users lets you ‘marry’ a bot, https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/japan/japanese-startup-loverse-ai-dating-app-b2579818.html